Some health experts around the world have been warning about a new wave of the coronavirus pandemic but another group is reluctant to label the rise in cases a "second wave", arguing that it is too soon to predict how the situation will pan out.

According to Euronews, the World Health Organization warned in late August that the COVID-19 outbreak in Europe is a "tornado with a long tail" and said rising case counts among young people could eventually spread to more vulnerable older people and cause an uptick in deaths.

Speaking from the WHO Europe headquarters, Dr. Hans Kluge said that 32 out of 55 states and territories in the global health body's European region have recorded a 14-day incidence rate increase of over 10%.

The UN health official called that "definitely an uptick which is generalized in Europe".

The Conversation reports that positive cases of COVID-19 have been continuously increasing in countries that previously had the spread of the virus under control—including Spain, France, Italy, and Germany—since the lifting of lockdowns at the start of summer.

Regardless of whether it is called a "second wave" or not, the question is how concerned should Europeans be about the resurgence in infections?

To answer this question, The Conversation asked experts in Spain, France, and the UK about the meaning behind these numbers and how health authorities in Europe should respond.

Read more: Shared Mobility Poised to Make a Comeback After COVID-19

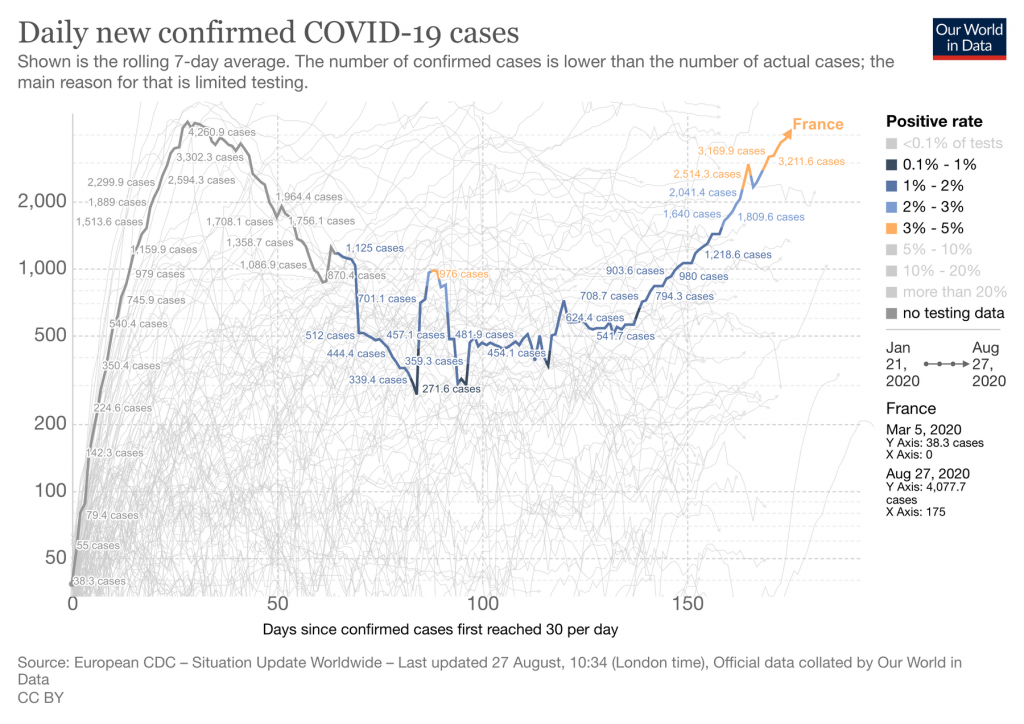

France

Dominique Costagliola, epidemiologist and biostatistician from Inserm says they have observed an increase in daily confirmed positive cases since mid-July.

According to her, a total of 5,429 new cases were detected between August 25 and 26.

"It doesn’t make much sense to compare these numbers with the numbers from March, because the situation is very different when it comes to testing. At the time, only patients with severe symptoms were screened, which is no longer the case. In spring, the number of actual cases was therefore much higher than those recorded."

The expert believes that the screening program was initially too limited and too slow. She adds that the number of cases is increasing more than the number of tests.

"In France, since July 20, anyone aged 11 and over must wear a general public mask in closed public places, including in schools. The main problem is that this obligation mainly concerns places open to the public. Wearing a mask should be compulsory in all enclosed spaces, whatever they are, as long as they cannot be ventilated."

Costagliola explains that herd immunity, which would slow the circulation of the virus, will be very difficult to achieve.

She argues that the only way to avoid a runaway epidemic, for now, is to manage the circulation of the virus at an acceptable level.

In her view, widespread, rapid screening, and monitoring of contacts as well as respect for social distancing measures can help achieve this end.

"This balance is not easy to maintain, but it is our only option for the months to come."

Read more: Ending COVID-19 Lockdowns Not Enough for Economic Rebound

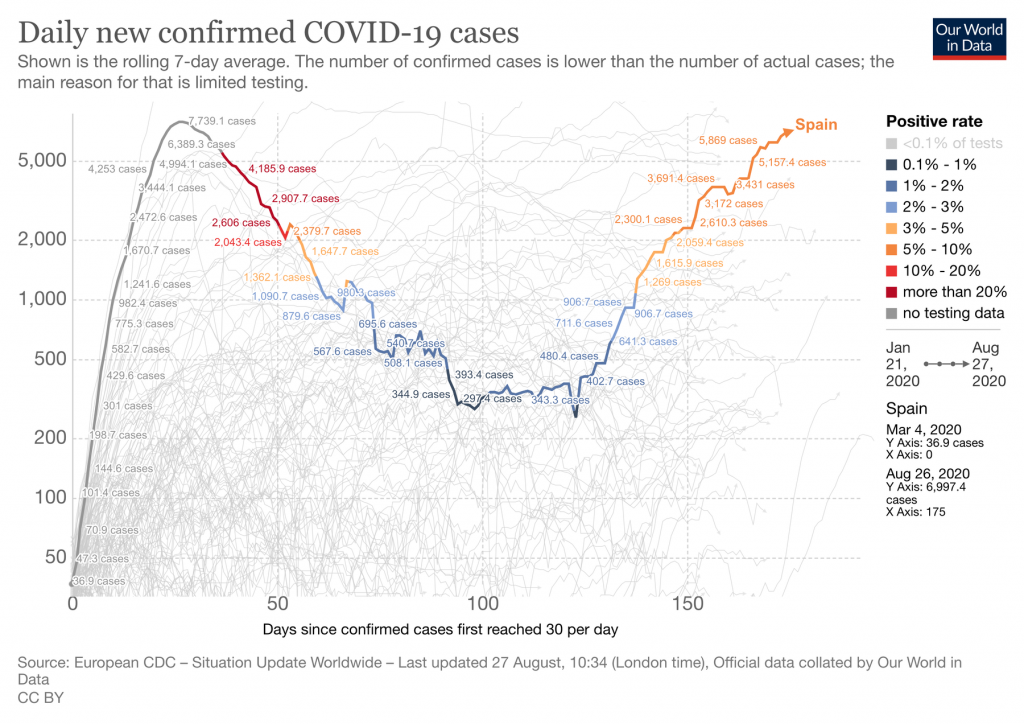

Spain

Ignacio López-Goñi, professor of microbiology at the University of Navarra, says more than 900 deaths per day were registered from the COVID-19 in Spain in the worst moments of the pandemic—between the end of March and the beginning of April.

"Strict confinement measures reduced the number of cases (defined as a positive result in a PCR test) to a minimum of a few hundred daily in mid-June. However, in recent weeks, Spain has reported a significant increase in the number of daily cases," he added.

According to López-Goñi, it is very difficult to find updated data on the number of hospitalized cases and deaths, which are the most important figures medical experts need to interpret the situation.

He says the reasons are that there is no consensus on COVID-19 case definition between countries and there are incomprehensible data discrepancies between Spain's autonomous communities and the federal ministry.

In his opinion, the current situation is not "alarming" but the trend can be described as "very worrying" because new outbreaks are detected every week.

"On one hand, it is reassuring to think that, at the moment, the virus appears to be relatively stable and is not accumulating mutations that affect its virulence—more deadly second waves in some influenza pandemics were associated with genetic changes in the virus."

However, he says the disturbing truth is that the population does not present immunity for the novel coronavirus, which could favor the appearance of a new wave.

Emphasizing the importance of strengthening control, López-Goñi said contagion should be prevented at all costs on the part of individuals with masks, social distancing, good hygiene, and trying to avoid crowded, indoor spaces.

"As for the health authorities, they have no choice but to take the lead. The virus does not care if we call this an outbreak, a flare-up, or a second wave. The virus does not recognize our internal or external borders. We need coordination, tracking, quarantine and isolation, and the strengthening of our primary care system. And we must by all means necessary avoid the virus reaching our hospitals again," the expert noted.

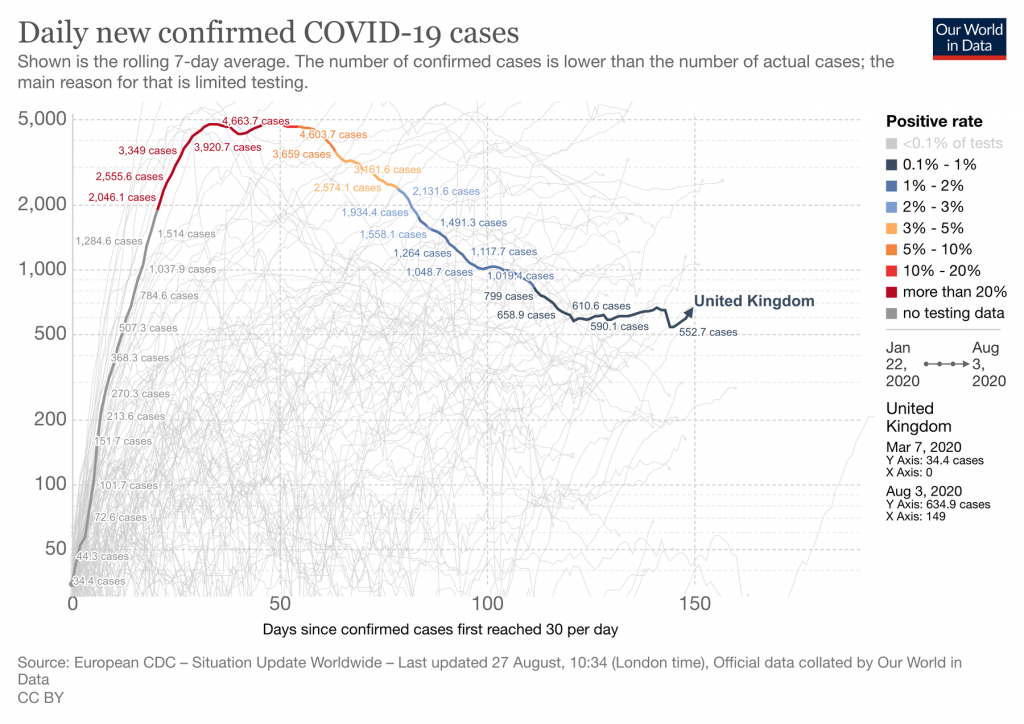

UK

Jasmina Panovska-Griffiths, senior research fellow and lecturer in mathematical modeling at UCL, says 327,798 people had tested positive for coronavirus and there had been 41,449 deaths associated with COVID-19 as of August 26 in the UK.

According to her, rising case numbers could mean three different things.

"First, it is possible that this is the second wave of COVID-19. Second, it could mean that the disease is spreading in clusters as localized outbreaks. Or, third, the rising numbers may show that relaxing lockdown restrictions have ended the suppression of what the WHO has called one big COVID-19 wave that will oscillate over time."

She believes it is currently too early to say which of these scenarios the UK is facing.

"A second wave in the UK would imply a large surge in the epidemic metrics, such as the number of new infections, hospitalizations, or deaths associated with coronavirus," the expert added.

She says a second wave is very much a possibility as additional waves have characterized all of the last four pandemics—the 1918 Spanish flu, the 1957-8 Asian flu, the 1967-8 Hong Kong flu, and the 2009 swine flu.

"Notably, although we have seen a rise in the number of new cases in the UK, the number of deaths and hospitalizations associated with COVID-19 has not increased."

Panovska-Griffiths says one potential reason is that the recent increase in the number of new cases is partly being seen in younger people now, who are at a lower risk of hospitalization and of dying from the disease.

"The UK has also increased its testing capacity since the onset of the epidemic, which is bound to bring up the number of confirmed cases," she added.

The expert noted that her recent modeling work suggests that a second wave associated with reopening schools, alongside reopening society, can be avoided if enough people with the symptomatic infection can be tested and their contacts traced and effectively isolated.

"An effective test-trace-isolate strategy could also work if, instead of facing a large second wave, we are faced with smaller local outbreaks come September," Panovska-Griffiths commented.