The Choice of Using EVMs

Conducting elections with the paper ballots, the dominant form of electing governments, has always been faced with many problems. With the intention of overcoming these problems, some countries either adopted or considered adopting the use of EVMs, taking into consideration some of the perceived advantages of using them in the elections. The use of paper ballots for nationwide elections – such as the presidential or parliamentary ones – could be exceedingly long. The paper ballot process takes longer time in transmitting the results, as paper ballots mean the symbols and names of hundreds of candidates have to be printed on dozens of pages for polling stations scattered across the country. On the other hand, the introduction of the EVMs was aimed at simplifying this very complex issue with the ballots. It was supposed to reduce the time required to count the voting results, as there are less paper and transportation involved. The concept of EVMs is often boasted by its proponents as a cost-saving measure compared to the method of using paper ballots, which is deemed to be costlier, as the paper ballots would have to be printed and then transported to all the polling stations across the country. The proponents of EVMs bring in another reason for using them. The public enthusiasm for digitization through EVMs could boost turnout in an era of waning voter turnout. What’s more, it was thought that if a government goes further than the EVMs and introduces other forms of e-voting system such as online voting, people might find it easier to vote from home, and hence, there’s likely to be a substantial increase in voter turnout. The e-voting systems are used in the biggest democracies like Brazil, India and the Philippines, in order to avoid the problems associated with the paper ballots and to take the perceived advantages that could be obtained from using EVMs and online voting. Indeed, it is the developing emerging economies from Asia and South America that are adopting e-voting — both EVMs and online voting, while e-voting is either being rejected or on the way out in most countries in the western hemisphere. These developing countries’ ruling parties intend to show to the public at large that with the e-voting systems, they are trying to further the democratic credentials, increase voter engagement and bring about technological growth.Challenges to the EVMs

Despite these ‘perceived’ advantages of the EVMs over the ‘proven’ disadvantages of the paper ballots, the use of the EVMs as a method of electing governments has substantially failed to become the dominant method for conducting elections. Only about one-fifth of 120 countries in the world – using voting as a method of electing governments – have experimented with, or used, EVMs to elect governments. Countries rejecting the e-voting – which are dominant in numbers – refer to the vulnerabilities of this new age voting system. This is perhaps because, the switch from paper ballots to e-voting does indeed remove the problems inherently associated to the paper ballots, including the cost of printing and distributing millions of ballots to polling stations in distant cities as well as remote areas. But the switch to the e-voting system introduces problems of its own.Technical & Technological Glitches

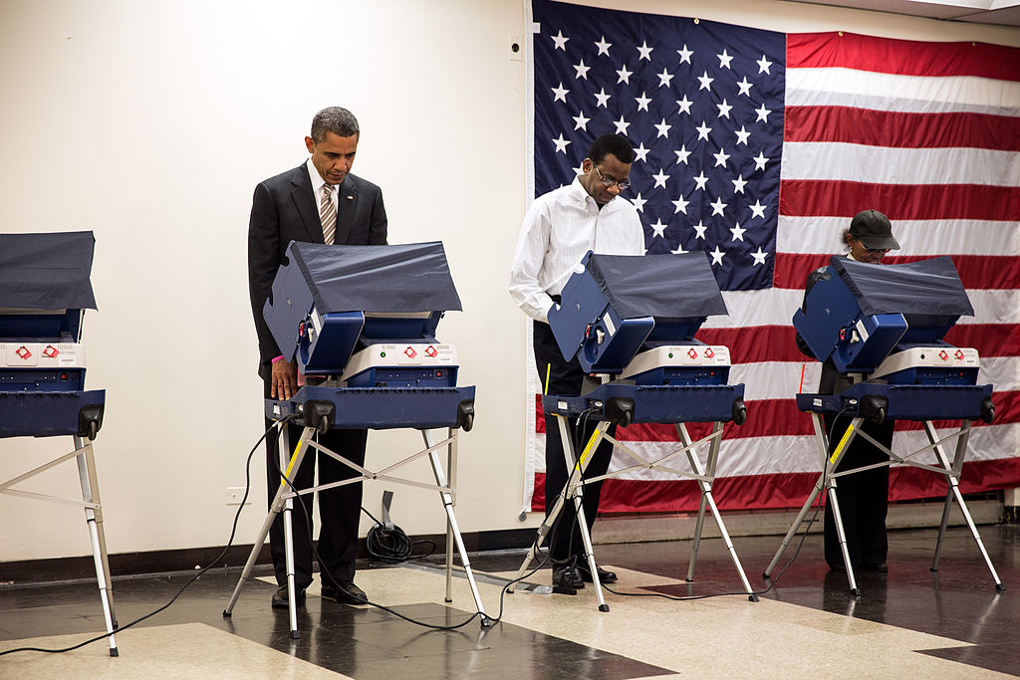

Technical and technological risk of malfunctioning of the e-voting systems, including the EVMs, is considerably high. During the recent voter registration process in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), many machines broke down and several days of repairing followed. This has raised the concerns that the potential for such malfunctioning is much higher during any elections anywhere in the world, including DRC’s elections in coming December. What happens when something goes wrong with the EVMs? There’s no easy way to trace the root of the problem with e-voting or EVMs. Even if the core of the problem could be identified, it would take considerable time to fix the problem (provided the problem is fixable at the first place). In such circumstances, the only way generally left to the election conducting bodies is to go for a recount of the votes, which bring about a number of new challenges. For instance, during the 2013 Kenyan presidential election, the biometric identification kits broke down, a server used for recording results was jammed, and election workers forgot the passwords and PIN numbers for software. All these resulted in the decision to count ballots with hands, delaying the results by nearly a week. Similarly, when the computerized machines deleted, deducted, and multiplied several votes during the USA presidential elections in 2004, a large number of these votes could never be recounted due to these machines’ inability to trail any paper audit. [caption id="attachment_5436" align="aligncenter" width="1020"] United States President, Barack Obama, casts his ballot in the 2012 U.S. election at the Martin Luther King Jr. Community Center in Chicago, Illinois. Photo by: Pete Souza.[/caption]

Furthermore, the recounting of the votes could require thousands of people – with overtime payment – working night and day to finish the counting. Something similar to this has happened in Tower Hamlets during the 2014 local elections.

Such recounting of votes brings about further challenges, as the EVMs runs on batteries. These batteries – however powerful they may be – need to be recharged once battery-life is over. This makes any extension of the elections difficult.

Even if there’s the option to charge the battery when it is still installed into the EVMs, there still remains the concerns that the EVMs batteries cannot be charged properly due to the load-shedding, which is an intentionally engineered electrical power shutdown where electricity delivery is stopped for non-overlapping periods of time rotationally over different parts of the distribution areas. Load-shedding is very common in rural and suburban areas in many parts of the world, including African, South Asian and Southeast Asian countries.

United States President, Barack Obama, casts his ballot in the 2012 U.S. election at the Martin Luther King Jr. Community Center in Chicago, Illinois. Photo by: Pete Souza.[/caption]

Furthermore, the recounting of the votes could require thousands of people – with overtime payment – working night and day to finish the counting. Something similar to this has happened in Tower Hamlets during the 2014 local elections.

Such recounting of votes brings about further challenges, as the EVMs runs on batteries. These batteries – however powerful they may be – need to be recharged once battery-life is over. This makes any extension of the elections difficult.

Even if there’s the option to charge the battery when it is still installed into the EVMs, there still remains the concerns that the EVMs batteries cannot be charged properly due to the load-shedding, which is an intentionally engineered electrical power shutdown where electricity delivery is stopped for non-overlapping periods of time rotationally over different parts of the distribution areas. Load-shedding is very common in rural and suburban areas in many parts of the world, including African, South Asian and Southeast Asian countries.

Ballot Secrecy and Voters’ Unfamiliarity with the EVMs

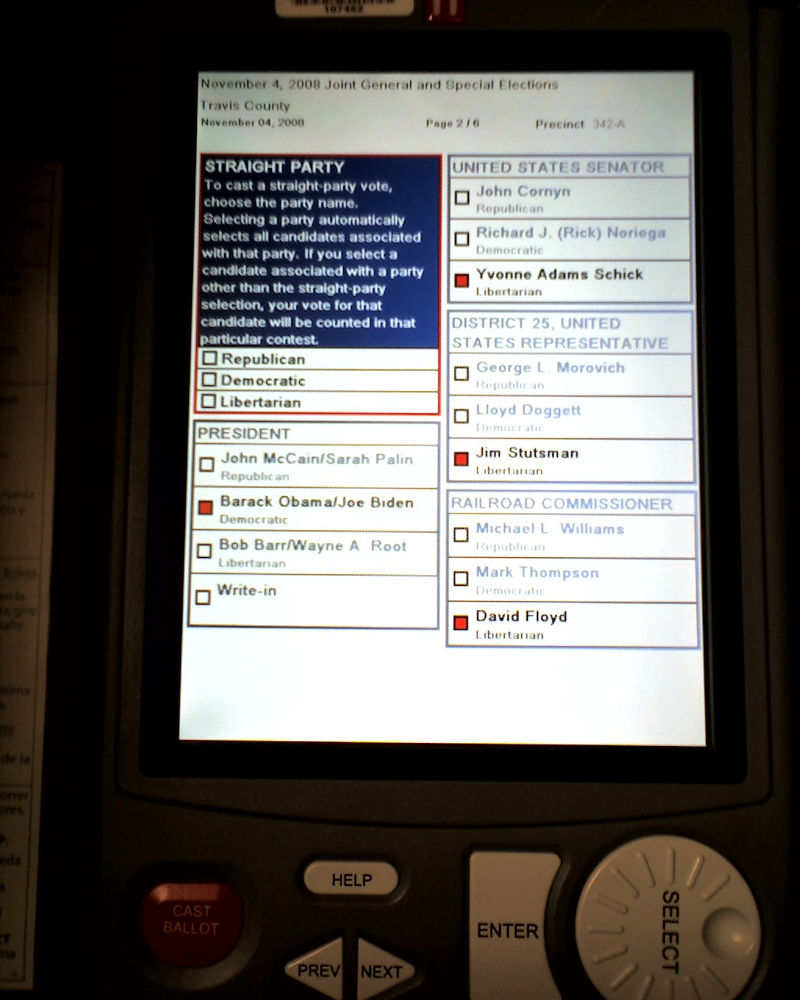

Countries that have adopted nationwide e-voting, including EVMs, are mostly developing countries. These countries have comparatively little democratic experiences, low literacy and inaccessible rural populations. Hence, voters have to rely on either known faces or electoral officials when casting their votes. These persons help the voters to swipe and tap the voting cards into the machines until they find their candidate. This certainly compromises the secrecy of the voting, with the possibility of a person knowing who the other person is voting for. One member of DRC’s pro-democracy youth movement ‘Lucha’, Fred Bauma, believes that officials could exploit such unfamiliarity with the technology to influence votes in the DRC’s elections due in the coming December this year. The majority of the voters in the Congolese remote areas are illiterate and do not know the use of EVM technology. Furthermore, touchscreen EVMs are intended to be used in coming DRC’s election. The outgoing USA’s ambassador to the United Nations (UN), Nikki Haley, raised an important question, “Will voters, many of whom have never used a touch-screen, know how to use them?” “It should go without saying that employing an unfamiliar technology for the first time during a crucial election is an enormous risk,” she continued. “It has the potential to seriously undermine the credibility of elections... .” [caption id="attachment_5441" align="aligncenter" width="800"] US election: Touchscreen EVM. Photo by: Tim Patterson.[/caption]

Touchscreen EVMs are not only intended to be used in the DRC but also is being used and proposed to be used in other countries as well. The use of these touchscreen voting machines increases the risk of flipping votes. This could happen when a voter touches the screen to choose a certain candidate, but the screen shows a different candidate selected due to error or maliciousness. This leaves little or no chance of recovering the vote, as the mistake could unlikely be detected.

Adding a new technology to the voting booth would require education not only for the electorates but also for the election conducting body’s officials who would have to be trained in the use of EVMs.

Mahbub Talukder, an Election Commissioner in Bangladesh, rejected the decision of using EVMs in the coming national (parliamentary) election in Bangladesh referring to the reason, among others, that the training of the officers is inadequate for using the EVMs during the national polls.

Even in the DRC, experts have been saying that the election officials would also have to be trained to use the 84,000 EVMs before the coming Congolese national election in December, which is a very short time for preparations.

US election: Touchscreen EVM. Photo by: Tim Patterson.[/caption]

Touchscreen EVMs are not only intended to be used in the DRC but also is being used and proposed to be used in other countries as well. The use of these touchscreen voting machines increases the risk of flipping votes. This could happen when a voter touches the screen to choose a certain candidate, but the screen shows a different candidate selected due to error or maliciousness. This leaves little or no chance of recovering the vote, as the mistake could unlikely be detected.

Adding a new technology to the voting booth would require education not only for the electorates but also for the election conducting body’s officials who would have to be trained in the use of EVMs.

Mahbub Talukder, an Election Commissioner in Bangladesh, rejected the decision of using EVMs in the coming national (parliamentary) election in Bangladesh referring to the reason, among others, that the training of the officers is inadequate for using the EVMs during the national polls.

Even in the DRC, experts have been saying that the election officials would also have to be trained to use the 84,000 EVMs before the coming Congolese national election in December, which is a very short time for preparations.

Cyber Security

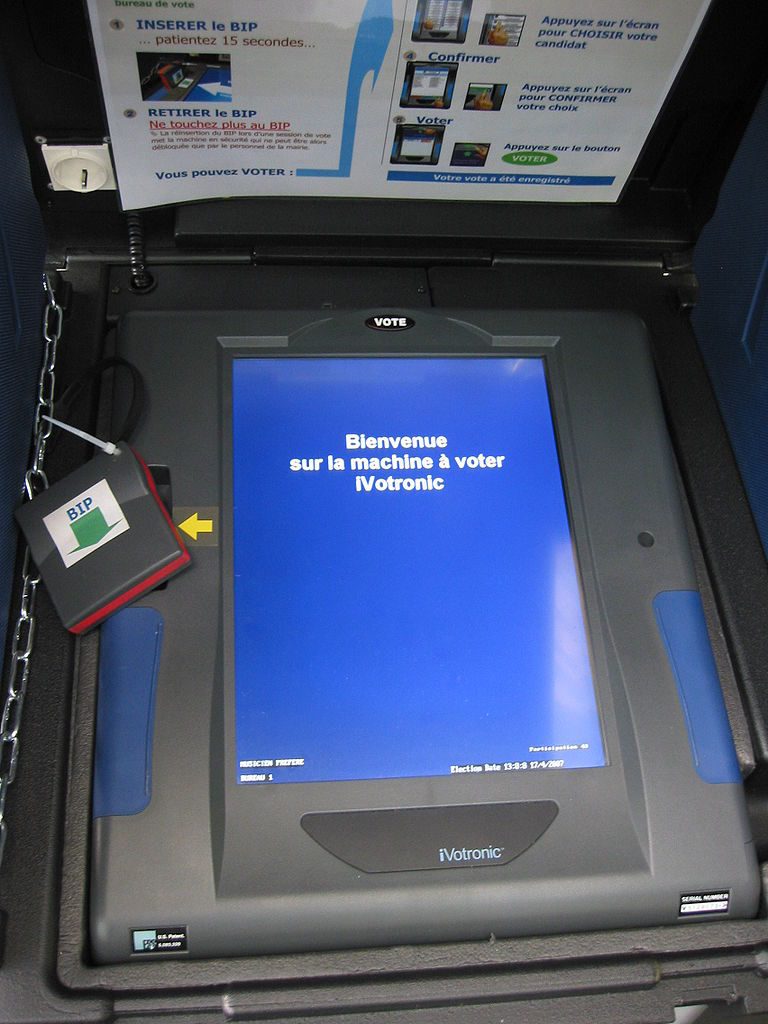

What makes the EVMs more vulnerable to cyberattack is when the machines are connected to a server and operate using the internet. This practice is common in almost all the countries using EVMs, including some states in the USA. In the last presidential election where Donald Trump came out victorious, it was alleged that there was Russian hand in influencing voters' choice, though this isn’t proven conclusively. Raila Amolo Odinga, the leader of Kenya’s opposition National Super Alliance coalition, alleged that the actual reason behind the cancellation of Kenyan presidential elections in 2017 was the hacking of the electoral body’s database to a substantial extent ‘to manipulate results’, though the visible reason was perceived to be the failure to comply with electoral management laws. In the same year, Argentina purchased EVMs from a South Korean firm named Miru for elections in 2017, though the machines were never used due to the security concerns including the EVMs’ vulnerability to hackers. Surprisingly, EVMs from the same South Korean firm are scheduled to be used in the DRC elections due in coming December, despite a team of high-profile experts have, in a published statement, categorically explained the technical and cybersecurity concerns of using EVMs during the election, including possibilities of hacking. The French nationals living abroad could vote over the Internet until France announced in 2017 that internet voting would not be allowed in the 2017 legislative elections due to “cybersecurity” concerns. [caption id="attachment_5442" align="aligncenter" width="696"] IVotronic voting machine used in Issy-les-Moulineaux during the election to the presidency of the French Republic in 2007. Photo by: Benoît Sibaud.[/caption]

Whereas in the Netherlands, the regulation for EVMs was withdrawn in 2008 following a Dutch parliament report, which was prompted after a Dutch pressure group’s revelation of the security flaws in the EVMs.

As with the USA, the country has been “remarkably slow” in “replacing voting machines most vulnerable to hacking”, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. What’s more, 41 states in 2018 “will be using systems that are at least a decade old, and officials in 33 say they must replace their machines by 2020”.

In India, a group of international and national experts presented during a conference a paper titled “Security Analysis of India’s Electronic Voting Machines”, where they have demonstrated two attacks using custom hardware, which corrupt election insiders or other criminals with even brief physical access to the EVMs could carry out.

[caption id="attachment_5437" align="aligncenter" width="750"]

IVotronic voting machine used in Issy-les-Moulineaux during the election to the presidency of the French Republic in 2007. Photo by: Benoît Sibaud.[/caption]

Whereas in the Netherlands, the regulation for EVMs was withdrawn in 2008 following a Dutch parliament report, which was prompted after a Dutch pressure group’s revelation of the security flaws in the EVMs.

As with the USA, the country has been “remarkably slow” in “replacing voting machines most vulnerable to hacking”, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. What’s more, 41 states in 2018 “will be using systems that are at least a decade old, and officials in 33 say they must replace their machines by 2020”.

In India, a group of international and national experts presented during a conference a paper titled “Security Analysis of India’s Electronic Voting Machines”, where they have demonstrated two attacks using custom hardware, which corrupt election insiders or other criminals with even brief physical access to the EVMs could carry out.

[caption id="attachment_5437" align="aligncenter" width="750"] Indian Electronic Voting Machine (2011). Photo by: பரிதிமதி.[/caption]

What’s more, Arvind Kejriwal, the star leader and Chief Minister of Delhi, went as far as challenging that an EVM could be hacked in 90 seconds. In the Delhi Assembly, his colleague, MLA Saurabh Bhardwaj went further and demonstrated how an EVM could be tampered with.

Indian Electronic Voting Machine (2011). Photo by: பரிதிமதி.[/caption]

What’s more, Arvind Kejriwal, the star leader and Chief Minister of Delhi, went as far as challenging that an EVM could be hacked in 90 seconds. In the Delhi Assembly, his colleague, MLA Saurabh Bhardwaj went further and demonstrated how an EVM could be tampered with.

Trust Deficit

Whether aforesaid allegations against the EVMs are right or wrong, there is certainly a huge trust deficit globally when it comes to using e-voting systems, including EVMs. In 2009, Ireland announced the scrapping of the EVMS – after marginally using them on a ‘pilot’ basis – due to lack of public trust, public dissatisfaction and opposition, and political controversy. In the DRC, the Congo Research Group and other research firms released a poll, where it appears that around 66 percent of Congolese were not in favor of EVMs. Furthermore, three of the major opposition parties recently made the desertion of EVMs as part of their three conditions to stay into the election process. Rushdi Nackerdien, Africa director for the International Foundation for Electoral Systems, said “these machines [in DRC] still need to be tested, configured, deployed and used in a tense mistrustful context.” In Bangladesh, when Chief Election Commissioner declared to use EVMs in the upcoming national election due in late December, one of the Election Commissioners, Mahbub Talukder, even sent a note of dissent, disagreeing to his superior’s decision. In reaction to the decision of using EVMs at national-level, a senior opposition leader, Barrister Moudud Ahmed, alleged that the government intends to indulge in corruption with EVMs procurement. He further alleged that such a move just three months ahead of the parliamentary polls is "a big conspiracy”. One other leader believes that the EVMs were “magic boxes of vote rigging”. India is one country where the suspicion over the continued use of e-voting system is running high. Following a meeting between Election Commission and all major political parties, the Congress leader Mukul Wasnik told the media that EVMs "do not reflect the will of the people". Indian frontline state-level leaders like Mayawati, Arvind Kejriwal, Saurabh Bhardwaj, Akhilesh Yadav, and Anil Dubey — all have been constantly voicing their concerns in meetings, protests and press and broadcasting media over the reliability of using the EVMs. Even during the last Assembly polls in an Indian state, Gujarat, the collector had to suspend Wi-Fi service of a college followed by a complaint from Congress nominee Ashok Jariwala. Ashok made similar complaint two days earlier. In this particular case, the issue of trust deficit was clear, as the complainant talked about his fear of tampering with the EVMs, using Wi-Fi. The collector too impliedly confirmed the trust deficit when he said, "to dispel their doubt, we have ordered its [Wi Fi] suspension."Trust Deficit in India despite VVPAT

With the intent to enhance transparency, India’s Election Commission had introduced the Voter Verifiable Paper Audit Trail (VVPAT), where a paper slip is generated bearing the name and symbol of the candidate for whom the elector has voted. However, both EVMs and VVPATs have become politically controversial since last year — something which has been already discussed in a number of cases earlier in this report.Online Voting

The problems of using EVMs appear smaller when compared with the other major form of e-voting, i.e. online voting or internet voting. Casting votes from home over the internet, there exits all the likelihood of the vote being stolen or forced, and secrecy of the ballot is compromised. These problems are so fundamental that no other country except Estonia has really cracked these problems, or at least this is what many prefer to claim about Estonia. In online voting, the internet gives electorates ease to vote from their homes using laptops or desktops, though these devices – like all other networked devices – are prone to sophisticated cyberattacks which can result in large-scale unnoticed rigging. Pointing to the downsides of internet voting, Jim Killock, the executive director of the Open Rights Group, argues that there’s the complexity of making sure that the voting equipment can be trusted despite being attached to the internet and that every voter’s machine is not being tampered with. “Given the vast numbers of machines that are infected by criminally controlled malware and the temptation for someone to interfere in an election, internet voting is a bad idea.”EVMs challenged in Europe

European democracies largely rejected e-voting. Six out of the eight European countries that have experimented with electronic voting returned back to paper ballots. The cases with Netherlands, Ireland, and France’s negative experiences with EVMs have already been mentioned earlier. Other European countries like Germany and Finland too didn’t have good experiences with the e-voting systems. Although Germany, the largest democracy in Europe, introduced electronic voting in 2005, there were subsequent reports of several layers of deficiencies with the EVMs. Subsequently, the Federal Constitutional Court banned EVMs in 2009 on constitutional ground, saying that since the EVMs system required the knowledge of programming that the citizens lacked, the system was 'opaque'. In 2017, the Finnish working group, launched with the purpose of studying Internet voting, recommended against Internet voting, concluding that the risks exceeded the advantages.Estonia, Brazil, Venezuela: E-voting-only success stories

Estonia was the first country to have ever passed a law in 2005 in order to make e-voting using the internet mandatory. Estonia had, for the first time, conducted a three-days-long Internet-based national election in 2007. [caption id="attachment_5438" align="aligncenter" width="800"] Electronic voting machine in Brazil (2014) Photo by: Mauro Cateb.[/caption]

Brazil, a populous country with over 200 million people, started using electronic voting in 1996. Brazil has the capability to declare the results within hours of conducting elections. Following Brazil’s lead, other American continent countries such as Mexico, Panama, Costa Rica, Venezuela, and Paraguay have all implemented some form of electronic voting.

Electronic voting machine in Brazil (2014) Photo by: Mauro Cateb.[/caption]

Brazil, a populous country with over 200 million people, started using electronic voting in 1996. Brazil has the capability to declare the results within hours of conducting elections. Following Brazil’s lead, other American continent countries such as Mexico, Panama, Costa Rica, Venezuela, and Paraguay have all implemented some form of electronic voting.

Paper ballots — a trusted, tested, transparent, and easy-to-use voting method?

During a UN Security Council meeting, which was mentioned above, Nikki Haley suggested that paper ballots are a “trusted, tested, transparent, and easy-to-use voting method" and asked the Congolese authority to abandon its plan to use the machines for the first time. In India too, paper ballots are increasingly seen as the right option to conduct major elections. With the parliamentary polls just months away, the opposition parties in late August 2018 tried to bring forward their concerns to the attention of the Election Commission (EC) and demanded a return to paper ballots, alleging that EVMs are being abused in favor of only the ruling party. Furthermore, 17 political parties are intending to move the EC with the demand of switching the election process from the EVMs to the paper ballots for the coming Lok Sabha (lower house of India's bicameral Parliament) elections in 2019. The trend of opposition to the EVMs is nothing new in India. When BJP, the current ruling party in India, was in the opposition, their top leaders too from questioned the EVMs’ reliability.Joseph Lorenzo Hall, an election technology expert from the Center for Democracy and Technology, said: “It’s basically consensus of most election officials and all the technical community and anyone else that works in election administration . . . that we should use paper.” According to an aforesaid published statement, the paper ballots are the most secure method of voting, while EVMs are prone to various vulnerabilities..@JoeBeOne: “It’s basically consensus of most election officials and all the technical community and anyone else that works in election administration . . . that we should use paper:"https://t.co/fgKI1j5CAI

— Center for Democracy & Technology (@CenDemTech) September 12, 2018

Observation

In light of the above findings, the following observations appear appropriate:- EVMs are being portrayed as the solution but may, potentially, make the electoral process worse.

- Counting paper ballots with hands, followed by double-checking, is more accurate than the EVMs.

- The potentiality for errors increases with the use of e-voting system, as technology is in a rapid pace constant evolution

- This understanding has led to trust-deficit globally among both voters and politicians.