Short-time work policies hold the promise of helping countries combat the economic crisis caused by COVID-19 if they are aided by high uptake, generous wage replacement, incentives, and higher flexibility, says an economist.

Michael Wolf from the Deloitte Global Economist Network cites short-time work—sometimes called a work-sharing program—as a policy that has gained considerable popularity among governments and policymakers in the wake of the pandemic.

"The details of short-time work schemes vary by country, but they generally aim to preserve the employer-employee relationship during temporary output disruptions by allowing employers to reduce worker hours even as the government subsidizes workers' lost wages," he wrote in a recent article.

Wolf believes that such an arrangement would enable businesses to preserve institutional knowledge while avoiding the lengthy and costly process of hiring and training new employees.

Read more: COVID-19 Mass Layoffs Brewing in Europe

The U.S.-based economist says short-time work programs can prove useful as they can restrain productivity when the economy is restarting.

"However, they are designed to be temporary measures and become less effective in a worst-case scenario where the downturn lasts years and creates a huge number of bankruptcies among companies."

In his view, schemes that are widely used, provide generous wage replacement, and encourage a quick and flexible return to work are the ones that will be successful in hastening a recovery when COVID-19 health risks eventually subside.

Policy there for the taking, but what's the uptake?

Only policies that are made widely available and are taken up by businesses and workers will be effective in the long run, Wolf says.

These policies should also be clear enough for both parties so that they can have confidence that the advantages of using the scheme are more than any potential costs.

"For example, the cost of laying off workers should be higher than the cost of keeping them under the scheme. In addition, companies should consider that they need to remain in business for the duration of the temporary disruption, which requires additional assistance for other fixed costs."

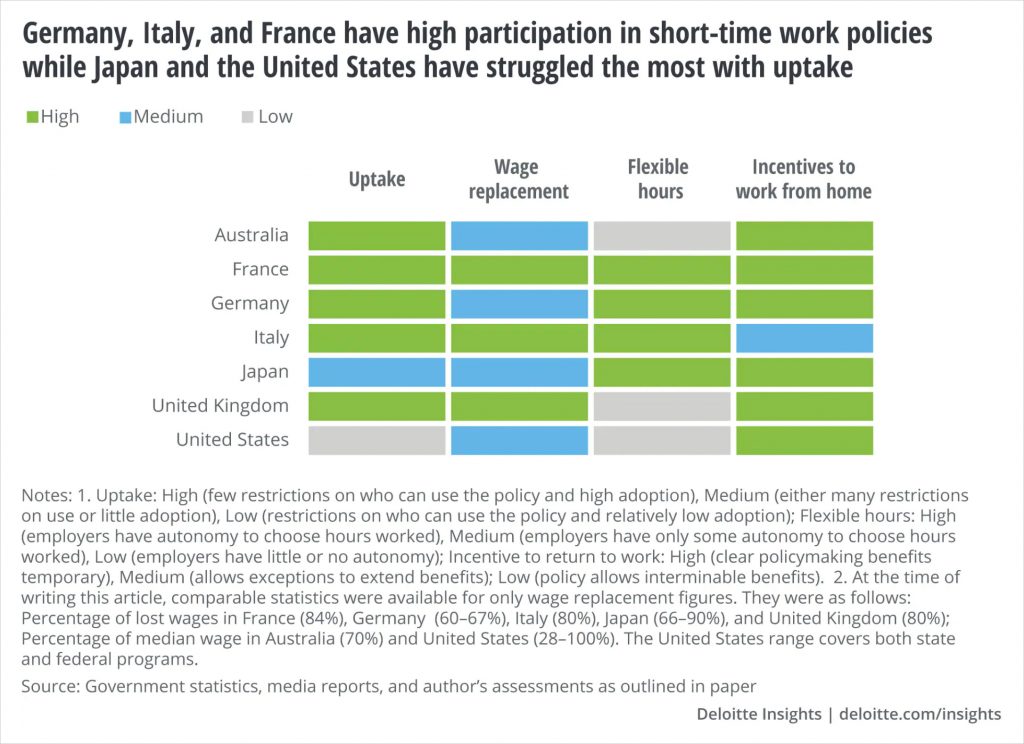

According to the Deloitte economic expert, countries such as Germany, Italy, and France—which had preexisting short-time work schemes—have been better positioned to get higher participation in the policies.

"Businesses and workers were already familiar with how these policies worked; the infrastructure for getting assistance was already established; and these countries’ governments made it costly to lay off workers. Italy even banned laying off workers altogether."

Although the United Kingdom and Australia are relatively new adopters of short-time policies, the number of workers participating in short-term schemes is rather high, with around 7.5 million workers in the UK and more than 6 million in Australia as of mid-May receiving the benefit, reads the article.

Wolf says Japan and the United States are the two countries that have struggled the most with the uptake of their short-time work schemes.

According to him, the scheme has been plagued with delays and red tape in Japan, and eligibility requirements in U.S. states are mostly ill-equipped to handle the severity of the current downturn.

"However, both Japan and the United States took steps in April to fix some of these initial problems so the uptake of their policies could eventually improve."

Generous wage replacement schemes can help arrest downturn

In another part of the article, Wolf says a short-time work scheme should reduce the fall in aggregate demand by providing funds to workers who would otherwise lose their job.

"In theory, this is similar to the effect of regular unemployment benefits. However, maintaining the attachment to an employer could give workers additional confidence about future earnings and therefore lead to higher spending relative to their unemployed peers," he added.

He maintains that countries that have a high uptake of the scheme and generous wage replacement rates are better equipped to prevent a more serious economic downturn.

"Italy and France offer relatively generous replacement rates for lost wages, roughly 80% each. Germany is less generous, replacing between 60% and 67% of lost wages. Under more normal circumstances, a less generous replacement rate may encourage a faster return to work; however, under the current circumstances, health risks should be the determining factor for the timing and magnitude of work resumption."

Read more: 78% of Startups Globally Plan to Hire by Year-End

According to the economist, replacement rates have been relatively generous in the UK and Australia as well.

"However, in both countries, these schemes are fairly new, and policymakers are already considering cutting the replacement rate as the crisis continues and the costs pile higher."

Wolf says that Japan, on the contrary, is increasing workers' wage subsidies and has recently taken steps to increase subsidies from around 60% closer to 100% for workers at small enterprises.

"In the United States, the state programs offer very low rates of replacement, while the federal program has the potential to offer much higher rates," he wrote, adding that this could render short-time work policies ineffective.

Hastening recovery: Flexibility is the key

Wolf regards flexibility and incentives to return to work quickly as the most important features of any short-time work scheme.

"Flexibility is critically important now, given that the ability to return to work will depend on health risks, which may ebb and flow, requiring employers to adjust the number of worker hours accordingly."

He says short-time work schemes in Germany, Italy, France, and Japan are designed in such a way that empowers enterprises with the discretion to navigate those ebbs and flows.

"The scheme in the United Kingdom was originally a furlough program, which required workers to be away from work entirely to qualify for its benefits, but policymakers have acknowledged the need to offer greater flexibility as businesses start to reopen," reads the article.

In Australia and the U.S., Wolf says, the schemes are operationally different from their counterparts in most of Europe and Japan, which can make it difficult to introduce flexible hours.

"Without additional modifications, Australia and the United States will find it more difficult to manage the tricky balance of returning to work amid changing health risks."

"Flexibility and incentives to return to work quickly as the most important features of any short-time work scheme."

Michael Wolf, a Deloitte expert

The Deloitte economist argues that experience shows that offering incentives to return to work as quickly as possible hastens the subsequent recovery.

"Otherwise short-time work schemes risk allowing low-performing businesses to hoard labor and stifle recovery," he said, adding that incentives to ramp up production become important only when health risks subside.

"Germany’s program, for instance, provides ample incentives as it requires businesses to pay into the scheme; charges more from those companies that have used it previously; and has them contribute to payroll taxes for hours not worked."

Wolf reiterates that short-time work schemes have the potential to support economies through recession and recovery if coupled with widespread adoption, generous benefits, flexibility, and incentives to return to work.